Introduction to periodontitis

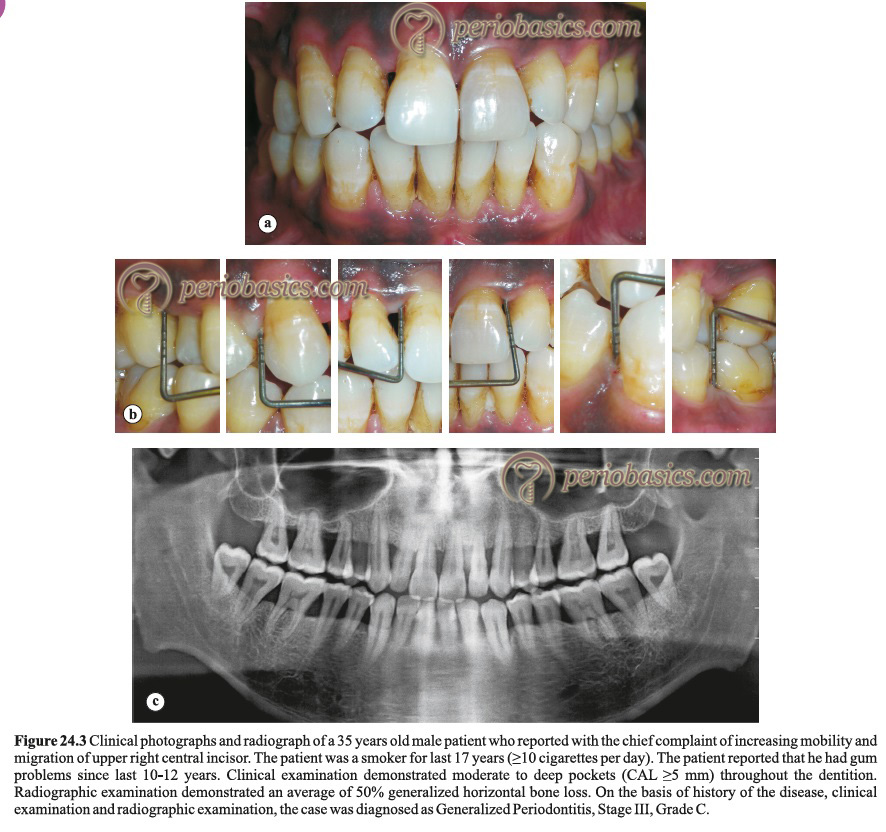

The 2017, World Workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions defines periodontitis as a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic plaque biofilms and characterized by progressive destruction of the tooth-supporting apparatus 1. This disease may progress rapidly or slowly and has been presently categorized in Stages and Grades according to the severity of periodontal destruction and risk of disease progression, respectively. In the 1999 classification system, periodontitis was classified as aggressive and chronic depending on the rate of disease progression. As the name indicates, aggressive periodontitis demonstrated rapid loss of periodontal supporting tissues over a short period of time and chronic periodontitis demonstrated a slow rate of disease progression. In the following discussion, we shall study in detail about this transition along with various aspects of periodontitis.

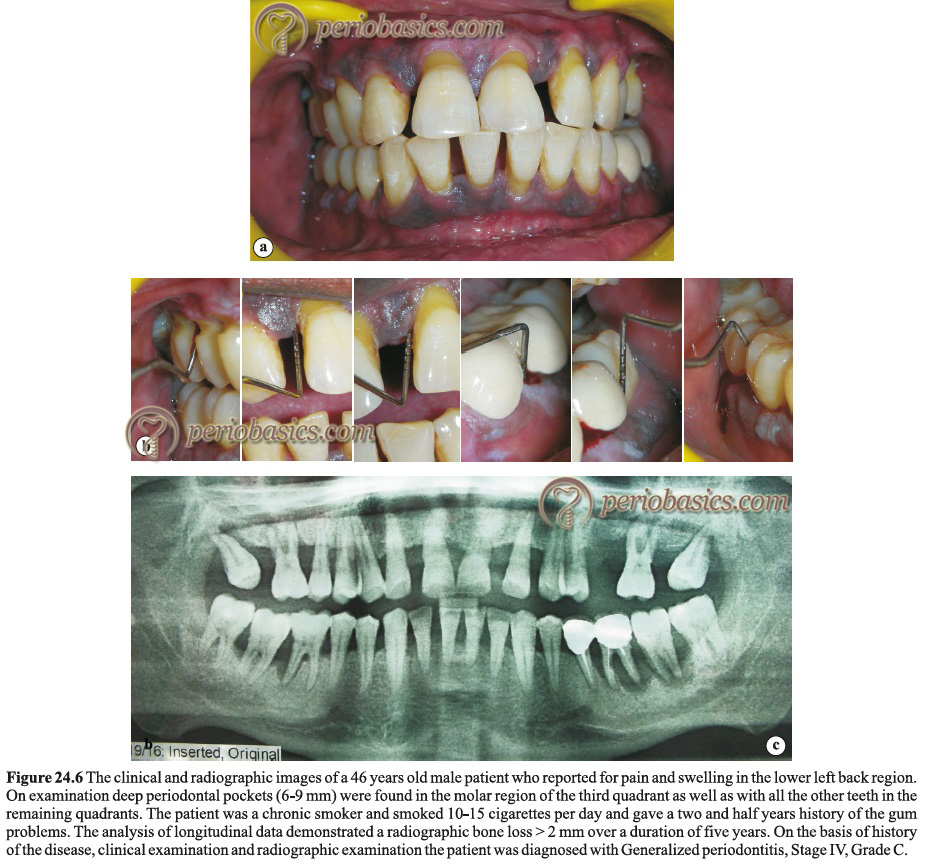

Criteria for diagnosing periodontitis

The World Workshop 2017, adopted the following criteria for defining a case of periodontitis 1,

- Interdental clinical attachment loss (CAL) is ‘detectable’ at ≥2 non-adjacent teeth, or

- Buccal or oral CAL ≥3 mm with pocketing >3 mm is detectable at ≥2 teeth.

Further, it has been clarified that the observed CAL cannot be ascribed to non-periodontal causes such as,

- Gingival recession of traumatic origin;

- Dental caries extending in the cervical area of the tooth;

- The presence of CAL on the distal aspect of a second molar and associated with malposition or extraction of a third molar,

- An endodontic lesion draining through the marginal periodontium; and

- The occurrence of a vertical root fracture.

Know More…

Chronic and aggressive periodontitis:

These terminologies were proposed by AAP World Workshop 1999 to explain two forms of periodontitis. Since all the research between 1999 to 2017 has been done under these two headings, it becomes essential to understand the criteria that were used to classify the chronic and aggressive periodontitis.

Chronic periodontitis was described as an inflammatory process that affected the protective and supportive tissues around the teeth. It was explained on the basis of scientific evidence that the primary etiology of this disease is the bacterial plaque on the tooth surface that leads to marginal tissue inflammation, known as gingivitis. Gingivitis is a reversible condition, but if left untreated, it may progress to periodontitis, which is characterized by loss of periodontal attachment (clinical attachment loss [CAL] / loss of attachment) and bone resorption, eventually resulting in tooth mobility and loss. The characteristic feature of chronic periodontitis is its slow progression rate. Although it may occur in any age group, but most commonly affected are adults and elderly people.

Aggressive periodontitis was described as a group of periodontal diseases characterized by localized or generalized loss of alveolar bone usually affecting the individuals under 30 years of age 13. It was described etiologically as a complex disease. Following characteristics were proposed to be associated with aggressive periodontitis 14.

Consistent characteristics:

1. Rapid attachment loss and bone destruction.

2. Except for the presence of periodontitis, patients are otherwise clinically healthy.

3. Familial aggregation.

Non-consistent characteristics:

1. Amounts of microbial deposits are inconsistent with the severity of periodontal tissue destruction.

2. Hyper-responsive macrophage phenotype, including elevated levels of PGE2 and IL-1β,

3. Phagocyte abnormalities.

4. Elevated proportion of Aggeregatibactor actinomycetemcomitans and in some populations Porphyromonas gingivalis may be elevated.

5. Progression of attachment loss and bone loss may be self-arresting.

Both chronic and aggressive periodontitis are further divided into localized or generalized forms:

Localized Chronic/Aggressive periodontitis: Periodontitis was considered as localized, when ≤30% of the sites assessed in the mouth demonstrate attachment loss and bone loss.

Generalized Chronic/Aggressive periodontitis: Periodontitis was considered as generalized, when >30% of the sites assessed in the mouth demonstrate attachment loss and bone loss.

Etiopathogenesis of periodontitis

As already stated, periodontitis is a multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic plaque biofilm. Its primary features include the loss of periodontal tissue support which is clinically manifested as clinical attachment loss (CAL) and radiographically manifested as loss of alveolar bone. The presence of periodontal pockets and gingival inflammation are the primary components of periodontitis. The primary etiology of periodontitis is microbial, but there are multiple risk factors that significantly affect the disease progression, including environmental factors like smoking and stress, systemic conditions like uncontrolled diabetes, variations in host immune response and genetic factors. Various putative periodontal pathogens have been identified that have a capability to evade the host immune response and cause periodontal destruction. As discussed in “Microbiology of periodontal diseases”, Gram-negative organisms of the “Red complex” including P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, and T. denticola are detected frequently in periodontitis patients 2.

More recently, the concept of microbial dysbiosis has been proposed, according to which periodontal pathogens can sufficiently modify their environment in a manner favorable for their survival, and stimulate microbial dysbiosis. Furthermore, dysbiosis may be a critical element in the switch from periodontal health to disease 3, 4. It has been demonstrated that P. gingivalis possess-es an array of virulence factors, including major and minor fimbriae, LPS, ceramides, gingipains, and others which support its role in the initiation of dysbiosis resulting in periodontal breakdown 5-8. Once the bacteria ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

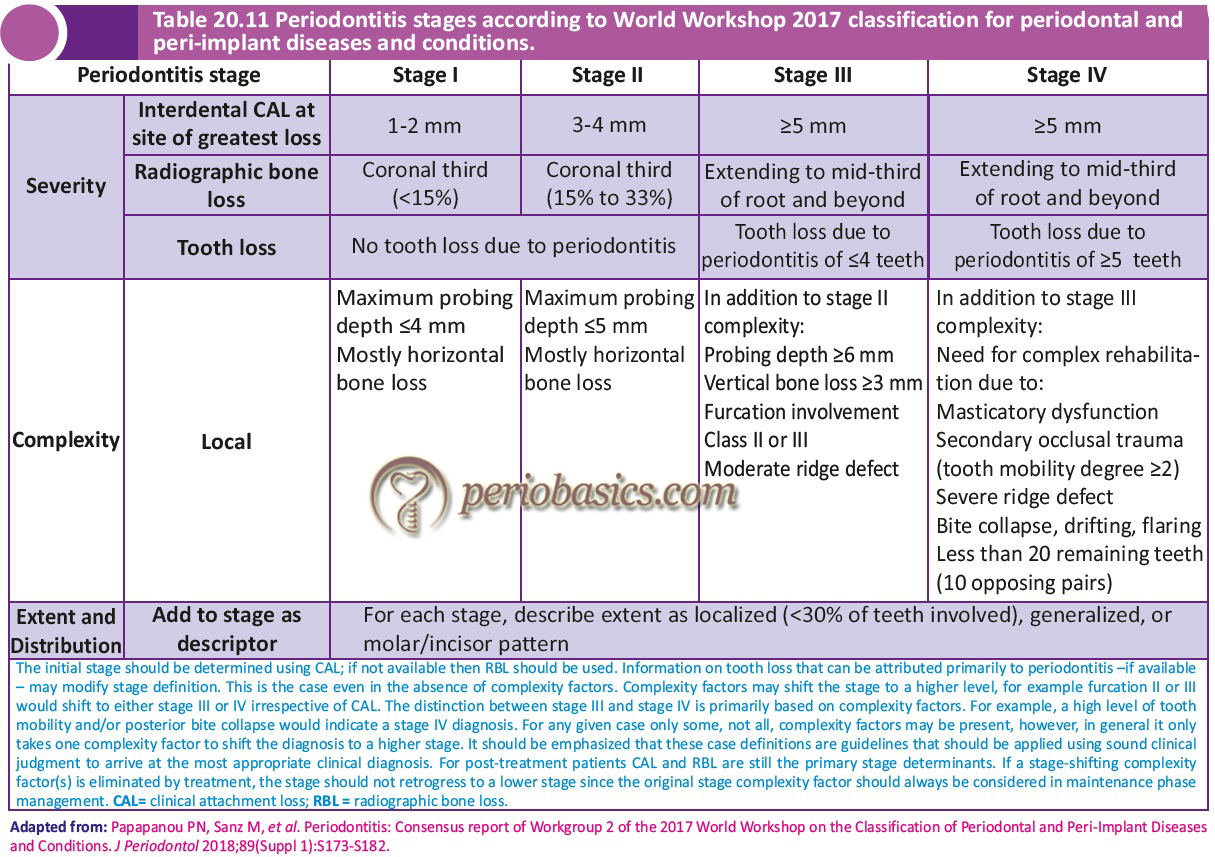

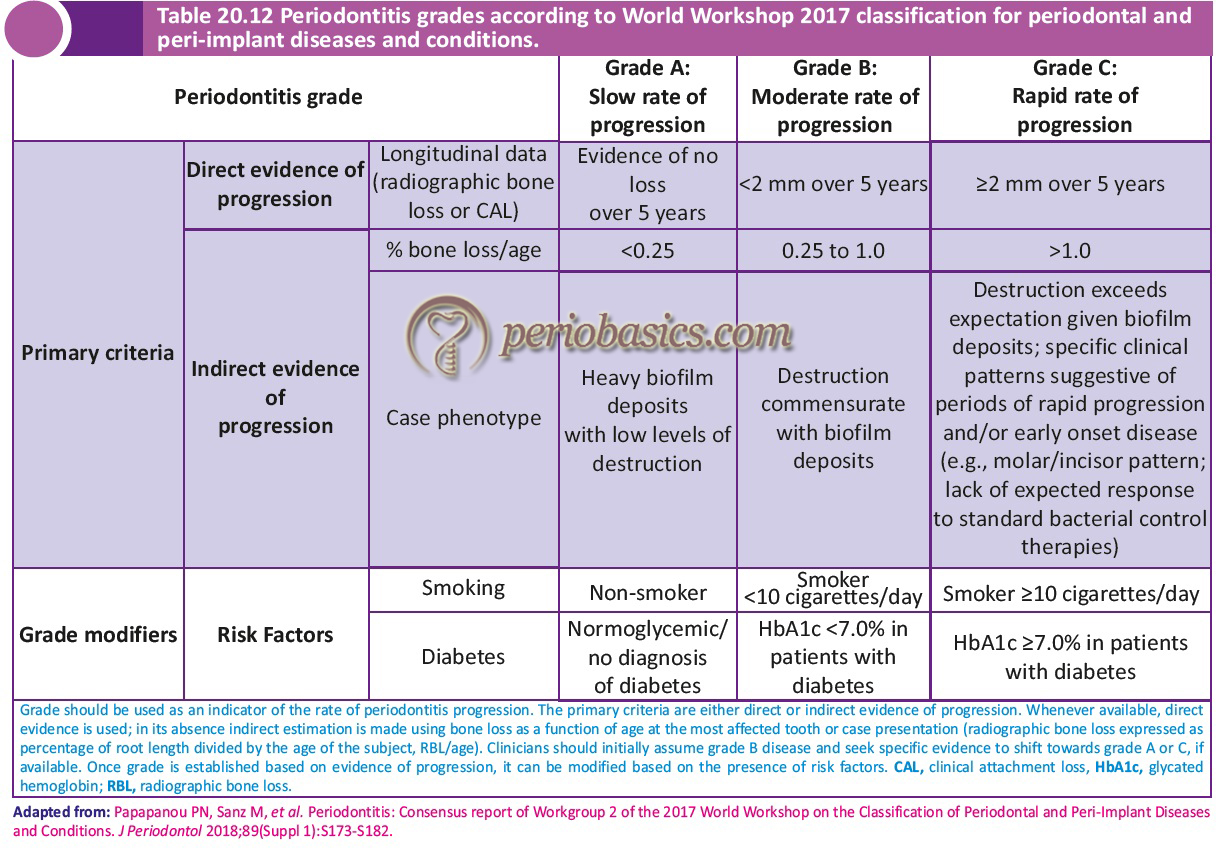

Staging and Grading system for periodontitis

As discussed in “Classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions”, the 2017 World Workshop has proposed the staging and grading system for periodontitis. The staging of periodontitis is dependent upon the severity of disease at presentation as well as on the complexity of disease management; whereas, grading of periodontitis provides us supplemental information about biological features of the disease including a history-based analysis of the rate of periodontitis progression; assessment of the risk for further progression; analysis of possible poor outcomes of treatment; and assessment of the risk that the disease or its treatment may negatively affect the general health of the patient 1. Following tables describe the staging and grading of periodontitis as proposed by World Workshop 2017. In the present discussion, the term chronic periodontitis from 1999 classification equates to Grade A and B periodontitis from 2017 classification and aggressive periodontitis equates to Grade C periodontitis.

Epidemiology of periodontitis

Epidemiology and risk factors for periodontitis with a slow to moderate rate of progression (Grade A and B) 15-17 and periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression (Grade C) have been extensively investigated 18, 19. One study estimated that the prevalence of periodontitis with slow to moderate rate of progression, in the age group 11-25 years is in the range of 1-3% in West Europe, 2-5% in North America, 4-8% in South America, 5-8% in Asia and 10-20% in Africa 19. Other investigations have demonstrated that race-ethnicity 20-23, gender 21, 24, 25 and socioeconomic status 24, 26 are important risk indicators for periodontitis with a slow to moderate rate of progression in adolescents and young individuals.

One study analyzed the data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) conducted on the USA population consisting of 9689 subjects. The authors concluded that pockets > 5 mm were found in 7.6% of non-Hispanic white subjects, 18.4% of non-Hispanic black subjects and 14.4% in Mexican Americans; a total of 8.9% of all subjects had pockets > 5 mm. Attachment loss > 5 mm was found in 19.9% of non-Hispanic white subjects, 27.9% of non-Hispanic black subjects and 28.3% of Mexican Americans; a total of 19.9% of all subjects had an attachment loss > 5 mm. The results of this study demonstrated that the severity of the periodontal disease is not uniformly distributed among race, ethnicity or the socioeconomic status 27.

One recent study was done on Brazilian population, where sample consisted of 612 individuals (291 males/321 females) aged 14-29 years. Full-mouth, six sites per tooth clinical examinations was performed. Chronic periodontitis was defined as CAL ≥3mm, affecting two or more teeth. Aggressive periodontitis cases were excluded from the analysis. Results showed that CAL ≥3 and ≥5mm affected 50.4% and 17.4% of subjects and 9.7% and 1.1% of teeth, respectively. Prevalence of chronic periodontitis ranged between 18.2% and 72.0% among subjects 14-19 years and 24-29 years of age, respectively 28.

Know More…

Historical background of periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression (Grade C periodontitis):

Periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression and severe destruction of alveolar bone was first reported by Gottlieb in 1923 29. He termed it as “diffuse atrophy of the alveolar bone”. The disease was characterized by loss of collagen fibers in the periodontal ligament and their replacement by loose connective tissue and extensive bone resorption, resulting in a widened periodontal space. He proposed that defect in the cementum formation was the primary cause of this disease which he considered an essential step for the maintenance of periodontal ligament fibers 30. This condition was then termed as “deep cementopathia”. The first molar-incisor involvement of the teeth was first described by Wannenmacher in 1938 31 which he termed as “parodontitis marginalis progressiva”. This disease was given name “paradontosis” by various authors who considered that it is a degenerative, non-inflammatory disease 32-34. However, the term ‘paradon-tosis’ was eliminated from periodontal nomenclature during the 1966 World Workshop in Periodontics 35. Later on, Chaput et al. in 1967 and Butler in 1969 proposed the term “juvenile periodontitis” to describe this disease 36.

This disease was described by Baer in 1971 37 as “a disease of the periodontium occurring in an otherwise healthy adolescent, which is characterized by a rapid loss of alveolar bone around more than one tooth of the perma-nent dentition. The amount of destruction manifested is not commensurate with the amount of local irritants”. In 1989, the World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics classified the disease as “localized juvenile periodontitis” (LJP), a subset of the broad classification of “early-onset periodontitis”(EOP) 38. The primary factors determining the diagnosis of LJP were the age of onset and distribution of the lesions. The 1999 World Workshop in Periodontics re-classified this disease as aggressive periodontitis to overcome the shortcomings of the earlier classification systems 39. However, with extensive scientific research it was realized that there was only a piece of limited evidence that differentiated the chronic and aggressive forms of periodontitis on the basis of specific pathophysiology. It was realized that there was little evidence in support of aggressive and chronic periodontitis being two different diseases. However, there was evidence in favor of multiple factors, interaction among which influences the clinically observable disease outcomes (phenotypes) at the individual level. So finally, during the 2017 World Workshop on periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions 40, both chronic and aggressive terms were discontinued and brought under a single heading “Periodontitis”.

Importance of case history

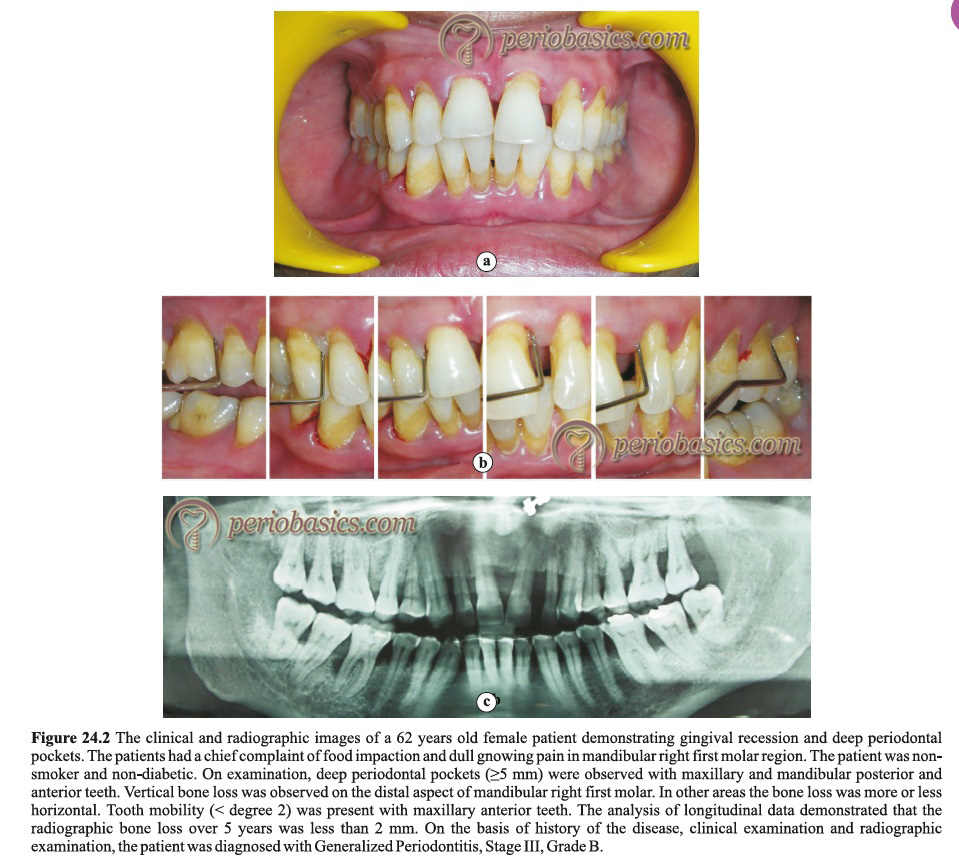

The first and foremost step in the diagnosis of periodontitis is a detailed case history of the patient. The duration of the disease can be established from the time, the patient first observed periodontal problem such as swollen gums/bleeding from gums/ bad breath/ dull gnawing pain deep in jaw bones/ mobility of teeth/ tooth migration, etc. In general, Stage III and Stage IV periodontitis are characterized by the widespread destruction of periodontal tissues usually in a young patient with the rapid rate of disease progression (Grade C) i.e. history of a couple of years. Whereas, Grade A/B periodontitis is associated with a slow rate of disease progression and is usually observed in older patients with a history of many years of disease progression.

In the case of generalized Stage III/IV, Grade C periodontitis most commonly reported complaints are ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Periobasics: A Textbook of Periodontics and Implantology

The book is usually delivered within one week anywhere in India and within three weeks anywhere throughout the world.

India Users:

International Users:

Clinical examination

Grade B periodontitis cases present with clinical features like supra-gingival and sub-gingival plaque accumulation which is consistent with periodontal destruction. Plaque accumulation is usually associated with calculus formation. It is prevalent in adults but may occur in children. Gingival inflammation is usually evident with pocket formation, loss of periodontal attachment and alveolar bone loss. Bleeding on probing can be seen from periodontal pockets. In these cases, gingiva may show a fibrotic appearance which is due to long-standing low-grade inflammation. This finding shows that there is sufficient time for repair following active periodontal destruction. Clinical attachment loss (CAL) is evident in the form of periodontal pockets or recession or both. In the case of multi-rooted teeth, furcation may be involved (Stage III and IV). In long-standing cases, tooth mobility or tooth loss may be evident. The disease can be classified on the basis of the rate of disease progression as slow (evidence of no loss over 5 years), moderate (<2 mm over 5 years), or rapid (≥2 mm over 5 years). The rate of disease progression may also be calculated as a percentage of bone loss/age with a slow rate of disease progression (<0.25), moderate (0.25 to 1.0) and rapid (>1.0).

Grade C periodontitis cases present with minimal supra- and sub-gingival plaque accumulation. Periodontal destruction is not consistent with the amount of local factors present (Figure 24.4). The patient is otherwise systemically healthy (systemic diseases may severely impair host defense leading to periodontal destruction). In cases of periodontal destruction due to systemic diseases, the diagnosis is usually made as a periodontal manifestation of systemic disease. The microbiological analysis shows elevated levels of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A. actinomycetemcomitans). Other characteristic features include phagocyte abnormalities and hyper-responsive macrophage phenotype, including the elevated production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in response to bacterial endotoxins. Active disease, as well as periods of inactive disease, are evident during the course of the disease. As described previously, periodontitis may be localized or generalized.

Disease progression

The disease progresses in alternating periods of activity and quiescence 41. Periods of quiescence may remain for weeks to months or even years and are followed by periods of active disease. During the periods of quiescence, patients are ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Microbiology of periodontitis

Periodontal diseases are primarily caused by periodontopathogenic bacteria for which they have been extensively studied 42-51. There are some fundamental problems in studying the microbiology of periodontal diseases. One major problem is the complexity of the microbiota of dental plaque of which only about 50-60% of the subgingival microbiota can be grown in the laboratory using standard culturing techniques. The remaining microorganisms are categorized as non-cultivable 52, 53. Secondly, it has been demonstrated by many studies that periodontally healthy individuals harbor some periodontal pathogens as a part of their normal supragingival and subgingival microbiota 54-61. These bacteria are present in relatively low number in healthy periodontal sites and they may be present in these sites for a long duration of time without causing disease. On the other hand, it has been suggested that the presence of these microorganisms is necessary for the development of immunity by the host 62.

Periodontal condition and most commonly associated microorganisms

| Periodontal Condition | Associated micro-organisms |

|---|---|

| Periodontal Health | Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus mitis, Actinomyces gerencseriae, Actinomyces naeslundii, Fusobacterium species, Prevotella nigrescens, Veillonella species. |

| Gingivitis | Lactobacillus species, Actinomyces naeslundii, Peprostreptococcus micros, Streptococcus anginosus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, P. intermedia, Winonalla parvula, Campylobacter species, Haemophilus species, Selenomonas Species, Treponema species. |

| Periodontitis with slow/moderate rate of progression (Grade A/B) | Eubacterium brachy, Eubacterium nodatum, Mogibacterium timidium, Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Parvimonas micra, Tannerella forsythia, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella loescheii, Dialister pneumosintes, Campylobacter rectus, Treponema species. |

| Periodontitis with rapid rate of progression (Grade C) | Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens, Eikenella corrodens, Selenomonas sputigena, F. nucleatum, Campylobacter rectus, Peptostreptococcus micros, Campylobacter concisus. |

| Refractory periodontitis | Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Streptococcus constellatus/intermedius, Tannerella forsythia, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, Campylobacter rectus, Eikenella corrodens. |

| Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis/periodontitis | Prevotella intermedius, Treponema species, Selenomona species, Fusobacterium species, Candida species. |

Another problem is the development of plaque as a biofilm. When bacteria grow in a biofilm, their characteristics are different from their planktonic counterparts. Different colonies in a biofilm communicate by quorum sensing which is important for the maintenance of internal environments in a biofilm. Horizontal gene transfer takes place in a biofilm between different organisms to sustain the virulence factor (details available in “Dental plaque”).

It is difficult to categorize any particular microorganism as the causative agent for periodontitis with slow, moderate or rapid rate of progression. However, attempts have been made to identify if there is any relationship between specific microorganisms with different forms of periodontitis. Various investigations done on identifying periodontal pathogens in chronic (Grade A/B) and aggressive periodontitis (Grade C) have been analyzed in a systematic review by Mombelli et al. (2002) 63 in which the authors concluded with no confirmation of any particular microorganism specifically associated with chronic or aggressive periodontitis. Here, it is important to remember that we are presently following the infection and host response paradigm. Our present knowledge strongly suggests that the host response is equally important for periodontal disease progression. Studies have shown that some of the bacterial species are strongly associated with advanced periodontal lesions. These include A. actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythensis and Treponema denticola 64. Many other studies have identified A. actinomycetemcomitans along with immunological defects as the main causative agent of localized Grade C periodontitis 65, 66. Although periodontitis is a result of a multi-bacterial infection and many bacteria are common in various forms of periodontitis, some authors have tried to categorize bacteria which are more prevalent in periodontal health, gingivitis, periodontitis with a slow / moderate rate of progression (chronic) and periodontitis with rapid rate of progression (aggressive) 67-70. Present evidence suggests that there are few bacterial species referred to as ‘keystone pathogens’ which play a key role in disease progression (see ‘Dental plaque’).

Immunology of periodontitis

Innate immunity:

In innate immunity, the role of neutrophils, Toll-like receptors and defensins has been well studied.

Role of neutrophils in periodontitis with a slow/ moderate/rapid rate of progression:

Polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) appears to play a key role in the maintenance of the periodontal health 71. Individuals with defective PMN function are subjected to increased periodontal breakdown (for more details read “Role of neutrophils in host-microbial interactions”).

Neutrophil function in periodontitis with a rapid rate (Grade C) of progression:

There are two kinds of neutrophilic function defects that have been discussed in the literature. One is impaired neutrophil function and the other is primed ⁄ hyperactive neutrophil func-tion. Both of these functions are opposite to each other. In the former, the neutrophil is unable to do its normal functions such as chemotaxis and phagocytosis whereas, in the latter, the neutrophil is hyperactive in its function.

Impaired neutrophil function:

There is strong evidence that neutrophils from localized or generalized periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression demonstrate defective chemotaxis and phagocytosis. There are many reasons suggested for impaired chemotaxis including reduced numbers of receptors on the neutrophil cell membrane, defects in neutrophil membrane receptors such as f-Met-Leu-Phe membrane receptor or its co-receptors such as GP110 (glycoprotein 110) or CD38, which participate in the chemotactic response. Neutrophils may also have a combination of a reduced number of receptors and defective receptors 72. A study demonstrated a significantly decreased expression of CD38 in f-Met-Leu-Phe-stimulated neutrophils in localized aggressive periodontitis (Grade C) patients as compared to normal individuals 73.

Various studies have demonstrated defective phagocytosis by neutrophils derived from a patient having localized or generalized form of periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression (Grade C). One study demonstrated that 53% of patients with localized Grade C periodontitis and 46% of patients with generalized Grade C periodontitis demonstrated neutrophils with the significantly lower percentage of phagocytosis per neutrophil as compared to neutrophils from Grade A/B periodontitis patients 74. In an in vitro investigation, it was observed that ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Hyperactive or primed neutrophil function:

As discussed above, various studies demonstrated defects in neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis, which could be either inherent and ⁄ or acquired, but these findings could not relate neutrophils to fully account for the rapid tissue destruction in Grade C periodontitis. Research in the last decade has emphasized on the presence of hyperactive⁄ primed neutrophils that could cause increased tissue destruction in localized/generalized Grade C periodontitis 81. These hyper-active neutrophils demonstrate increased adhesion and most importantly elevated oxidative burst. It has been demonstrated that neutrophils from patients with Grade C periodontitis have increased intracellular levels of β-glucuronidase, which is present in azurophilic granules of the neutrophils 82. Increased β-glucuronidase levels in GCF have been associated with increased periodontal destruction 83. Another important enzyme secreted by neutrophils, which actively participates in tissue breakdown is myeloperoxidase. The level of this enzyme in GCF sample of Grade C periodontitis patients have been found to be increased in areas with active periodontal destruction. A positive correlation between enzyme levels and presence of bleeding and suppuration has been found 84.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) participate in tissue remodeling by breaking down various components of the connective tissue. MMP-8 and MMP-9 are derived from neutrophils and have been investigated for their role in the tissue breakdown in Grade C periodontitis. Studies have demonstrated no significant difference in tissue or crevicular fluid levels of MMP-8 enzyme between Grade A/B and Grade C periodontitis patients 85.

Neutrophil function in periodontitis with a slow/ moderate rate (Grade A/B) of progression:

As already discussed, neutrophils have an important role in host-microbial interaction in periodontal diseases. Various aspects of neutrophil function have been investigated in periodontitis with slow/moderate rate of progression. Neutrophil cytokine release has been studied in Grade A/B periodontitis. As compared to healthy controls, increased plasma concentrations of IL-8 86, IL-6 87-90 and IL-1β 91, 92 have been demonstrated in patients with Grade A/B periodontitis. Similarly, increased GCF concentrations of IL-8 93, IL-6 94, IL-1β 91, 95 and TNF-α 94, 96 have been reported in Grade A/B periodontitis patients.

There are few studies done to investigate peripheral blood neutrophil cytokine release from patients with chronic periodontitis. Some of them have shown no difference in the release of cytokines (IL-8, IL-1β, and TNF-α) in Grade A/B periodontitis patients as compared to healthy controls 97, 98 while one study demonstrated decreased IL-8 release from isolated neutrophils of patients with Grade A/B periodontitis as compared to healthy controls 99. Another study demonstrated significantly more IL-1β release from neutrophils in patients with chronic periodontitis as compared to healthy controls 100.

A few investigations have been done to investigate neutrophil chemotaxis in Grade A/B periodontitis patients. However, conflicting results have been reported. Two studies have reported significantly increased chemokinesis of neutrophils towards E. coli supernatant, fMLP, and LPS-activated serum in Grade A/B periodontitis patients 101, 102 whereas two other studies have reported no significant difference between neutrophil chemotaxis in Grade A/B periodontitis patients and controls 103, 104. It has been hypothesized that periodontal disease pathogenesis may also be associated with dysregulated neutrophil extracellular trap release 105. However, more research is required to clarify the dysregulation of neutrophil extracellular trap release in Grade A/B periodontitis patients.

Role of Toll-like receptor (TLR) in periodontitis:

Toll-like receptor (TLR) family, plays a fundamental role in pathogen recognition and activation of innate immunity. Members of this family are responsible for the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) expressed by a wide spectrum of infectious agents. To date, ten proteins have been identified that belong to the human TLR family 106, of which TLR2 and TLR4 have been extensively studied. TLR2 has been identified as a receptor that is central to the innate immune response to lipoproteins of Gram-negative bacteria, several Gram-positive bacteria, as well as a receptor for peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid and other bacterial cell membrane products. TLR4 physically associates with another molecule called MD-2, and together with CD14, this complex is responsible for LPS recognition and signaling. It has been shown that TLR2 and TLR4 are expressed in the healthy oral epithelium but the expression of both is markedly upregulated during inflammation 107 TLR2 stimulation has been shown to be associated with Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharides and Gram-negative periodontal bacteria 108-110. A study done by Kikkert et al. (2007) 108 showed that only A. actinomycetemcomitans and Veillonella parvula were capable of stimulating both TLR2 and TLR4.

Various studies have investigated the expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in different forms of periodontitis. A study showed increased expression of both TLR2 and TLR4 in Grade A/B periodontitis (chronic periodontitis) cases as compared to healthy tissues where only a weak expression of TLR2 and no expression of TLR4 was detected 111. Various studies have demonstrated TLR2 and TLR4 mutations/ polymorphisms and their positive association with different forms of periodontitis 112-115, whereas, many others have not found any relation 116-118. So, this is a matter of further research at the molecular level to explain the exact mechanism of this association, if any.

Role of defensins in periodontitis:

The epithelium, along with acting as a physical barrier also contains substances that kill pathogens or inhibit their growth. Most abundant among them are the antimicrobial peptides, called defensins. Human defensins are divided into two subgroups: α- and β-defensins. Both α- and β-defensins consist of a triple-stranded β-sheet structure, and have a molecular weight between 3 to 6 kDa. Six alpha-defensins (hND-1 to hND-6) and four beta-defensins (hBD-1 to hBD-4) have been defined in humans.

α-defensins along with cathelicidin LL-37 are present in high levels in neutrophils that migrate through the junctional epithelium to the gingival sulcus, where they act as anti-microbial peptides. The oral sulcular, pocket and junctional epithelia of the gingiva are all associated with the expression of defensin, more specifically β-defensins hBD-1, hBD-2 and hBD-3 119. It has been shown that P. gingivalis stimulates hBD-2 expression in gingival epithelial cells 120. A significantly higher expression of hBD-3 has been demonstrated in patients with Grade A/B (chronic) periodontitis 121.

The levels of cathelicidin LL-37 were found to be reduced or absent and levels of neutrophil peptide 1-3 defensin were found to be reduced in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) samples derived from Grade C periodontitis (aggressive periodontitis) patients as compared to GCF samples derived from Grade A/B periodontitis (chronic periodontitis) patients 122. In another investigation, it was found that in neutrophils derived from patients with generalized Grade C periodontitis, levels of human neutrophil peptide 3 defensin were significantly reduced 123. However, in this study, it was proposed that reduced levels of neutrophil peptide 3 defensin had only a minor role in the pathogenesis of Grade C periodontitis.

Acquired immunity

The adaptive immune response in periodontitis has been extensively studied. It has been shown that Th1 cells play an important role in an early or stable lesion of chronic periodontitis whereas, advanced lesion of chronic periodontitis is dominated by B-cells and plasma cells, which are activated byTh2 cytokines 124-127. Details about Th1 and Th2 cell response can be studied in “Host-microbial interactions in periodontal diseases”. The role of acquired immunity has been discussed in details in the same chapter.

The difference in the acquired immune response in different forms of periodontitis appears to play an important role in the disease progression. Grade C periodontitis may not follow the same sequence of initiation and progression as Grade A/B periodontitis i.e. initial lesion dominated by T-cells to a progressive B-cell and plasma cell dominated lesion. This may be because of the reason that the clinical course of the disease in case of Grade C periodontitis is quite different from Grade A/B periodontitis. The basic functions of cells, which are involved in acquired immune response, e.g. TH0, Th1, Th2, Treg, Th17, etc. are discussed in,“Host-microbial interactions in periodontal diseases”.

Role of genetics in periodontitis with a slow/moderate/rapid rate of progression

Periodontitis with a slow/moderate rate of progression (Grade A/B):

Although research work has shown that genetic factors may be associated with Grade A/B periodontitis but no clear genetic determinants have been described 128. The twin model is probably the most powerful method to study genetic aspects of periodontal diseases. Initial studies recognized that the periodontal conditions of identical twins were often similar 129. In one of the largest twin study done by Corey et al. (1993) 130, 4908 twin pairs were studied using a questionnaire data. 349 (116 Monozygotic and 233 Dizygotic) pairs reported a history of periodontal disease in one or both pair members. The concordance rates ranged from 0.23 to 0.38 for monozygotic twins and 0.08 to 0.16 for dizygotic twins.

In another study Michalowicz et al. (1991) 10 studied the ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Periobasics: A Textbook of Periodontics and Implantology

The book is usually delivered within one week anywhere in India and within three weeks anywhere throughout the world.

India Users:

International Users:

Various single nucleotide polymorphisms have been shown to be associated with disease progression in chronic periodontitis cases. These include

Polymorphisms in the IL1 gene cluster,

Polymorphisms in the TNF-α gene,

Polymorphisms in the IL4 and IL4RA genes,

Polymorphisms in the IL6 and IL6R genes,

Polymorphisms in the IL10 gene,

Polymorphisms in the FcγR gene,

Polymorphisms in the VDR gene,

Polymorphisms in the Pattern Recognition Receptor genes,

Polymorphisms in the CD14 gene,

Polymorphisms in the TLR2 and TLR4 genes,

Polymorphisms in miscellaneous genes.

These polymorphisms have been described in detail in “Role of genetics in pathogenesis of periodontal diseases”.

Periodontitis with the a rapid rate of progression (Grade C):

Evidence in favor of an association between genetic link and periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression has been clearly established. The initial research work showed that the prevalence of Grade C periodontitis (aggressive periodontitis) was disproportionately high among certain families 36, 37, 132. One study done by Marazita et al. (1994) 133 in young patients with severe periodontitis showed that their siblings often suffered from severe periodontitis. These findings were followed by a systematic genetic research work which included three genetic analysis methods that can be used to study modes of inheritance: pedigree analysis, segregation analysis, and linkage analysis.

Pedigree analysis studies the transmission of disease in families from one generation to the other. Both X-linked dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance of Grade C periodontitis has been proposed. Many studies have shown an increased prevalence of Grade C periodontitis among female family members which supports the X-linked dominant inheritance 134-137. On the other hand, certain features like affected siblings of unaffected parents support autosomal-recessive inheritance of Grade C periodontitis 138, 139. Although different modes of inheritance have been proposed by different researchers, it is difficult to assess the mode of transmission in one family and the appearance of the disease in a particular individual 140.

Segregation analysis is based on Mendel’s laws 141. In this analysis, it is expected that the genes segregate from parents to their offspring’s in a predictable manner. For autosomal dominant inheritance the segregation ratios are 1:2 and for autosomal recessive inheritance these are 1:4. A segregation analysis study was done on families affected with Grade C periodontitis. The authors concluded that the mode of inheritance was most probably an X-linked dominant trait with a decreased penetrance of 78%, and the female:male ratio of affected persons was approximately 2:1 142.

Linkage analysis is based on the fact that alleles present in close proximity on a chromosome tend to be passed together from one generation to the other generation. These genes which are “linked” violate Mendel’s law of independent assortment. Boughman et al. (1985) 143 first reported linkage between Grade C periodontitis and a specific chromosomal region (4q11-13) near the gene for dentinogenesis imperfecta. Another linkage reported was of localized form of Grade C periodontitis to a marker on chromosome 1(1q25) 144. The linkage analysis of genetic variations in IL-1 was also associated with Grade C periodontitis 145.

Other studies which have shown a genetic link of Grade C periodontitis include,

- The study of inherited disorders and genetic syndromes.

- Twin studies.

- Population studies.

- Single nucleotide polymorphism.

Role of risk factors in the progression of periodontitis

Risk factors involved in the progression of periodontitis can be divided into two categories viz. modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Modifiable risk factors are those which can be eliminated or reduced such as smoking, which is a well-established modifiable risk factor. Whereas, factors like genetic factors, immunological abnormalities are designated as non-modifiable as they cannot be modified. Many risk factors are common to various forms of periodontitis including periodontitis with slow, moderate and rapid rate of progression. However, some risk factors have been shown to be particularly associated with periodontitis with rapid rate of progression. Following is the description of these risk factors,

Risk factors common to various forms of periodontitis

Prior history of periodontitis:

Prior history of periodontitis puts the patient at more risk of developing periodontitis. Periodontal bone loss is caused by the accumulation of microbial plaque. An improperly treated patient or patients with poor postoperative maintenance are the candidates, which can develop periodontitis even after treatment. Here lies the importance of bone re-contouring during periodontal surgery. The architecture of the periodontal tissues should be modified in such a manner that patient can easily maintain oral hygiene and there are minimal chances for re-pocket formation.

Age:

Usually, periodontitis with a slow to moderate rate of progression occurs in adults, although younger patients may be affected. The disease has a slow progression and patients usually present with a history of many years. So, it is expected that older patients are more commonly affected with slowly progressing periodontitis. On the other hand, periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression is usually observed in relatively younger patients. This is because alteration in the host immune response and genetic variations have been found to play an important role in its pathogenesis.

Oral hygiene:

Poor oral hygiene is a risk factor for the development of periodontitis. Many randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the cause-effect relationship of plaque on gingivitis 146-148. Application of antimicrobial therapy and agents such as chlorhexidine also reduces the gingival inflammation, which indicates the importance of maintaining good oral hygiene to reduce periodontal disease activity. Other investigations have shown that periodontal surgical procedures accompanied by regular professional tooth cleaning halt the progression of periodontal diseases 149-151. All these findings suggest that bacterial plaque is the primary risk factor for the development of periodontal disease and the maintenance of oral hygiene is required to return to periodontal health.

Smoking:

It is an important risk factor for periodontal disease progress-ion as well as response to periodontal therapy. Many investigations have shown that smokers have an increased prevalence and severity of the periodontal disease, as well as a higher prevalence of tooth loss and edentulism 152-158. The reported odds ratios for developing periodontal disease as a result of smoking are 2.5 159, 3.97 for current smokers and 1.68 for former smokers 160 and 3.25 for light smokers to 7.28 for heavy smokers 153. It has also been shown that periodontal treatment is less likely to be successful in smokers than in non-smokers 161, 162.

How smoking affects the periodontal disease progression has been discussed in detail in “Smoking as a risk factor for periodontitis”.

Stress:

Many clinical investigations have demonstrated a possible relationship between psychological stress and periodontitis and have suggested that stress may play a role in the development of periodontal disease 163-165. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the systemic adreno-medullary sympathetic nervous system plays an important role in periodontal disease progression. Details about this relationship have been discussed in “Stress as a risk factor for periodontal diseases”.

Gender:

It has been a consistent finding that the severity of periodontal diseases is generally more in males than in females. It is confirmed by all the national health surveys conducted in the United States 166-168. The reason for this variation is that males usually exhibit poorer oral hygiene than females, whether measured for calculus or soft plaque deposits. Poor oral hygiene is the basis of this variation in the severity of periodontal diseases between the two genders. So, gender may not be considered as an absolute risk factor, but poor oral hygiene must be.

Genetic factors:

Genetics and its role in periodontal disease have been well investigated and present data strongly suggest that genetic factors play an important role in the progression of periodontal diseases. Various genetic factors have already been discussed in the previous sections. The complete detail of genetic factors is available in “Role of genetics in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases”.

Role of systemic factors:

There is wide evidence in the support of the association of systemic diseases and periodontal diseases 169-175. Systemic diseases like diabetes not only influence the pathogenesis of the periodontal disease but also affect the course and the outcome of the disease. Healing and post-operative maintenance are also affected by systemic diseases. They play an important role in disease progression in periodontitis with slow, moderate or rapid rate of progression. So, they act as an important risk factor for periodontal diseases.

Socioeconomic Status (SES):

Studies have clearly demonstrated more prevalence of destructive periodontal diseases among people with low SES 167, 168. It is believed that well-educated people with good SES have better oral health status than the less educated and poorer segments of the society. The reason for this is the positive attitude toward oral hygiene and a greater frequency of dental visits among the more dentally aware and those with dental insurance. Gingivitis has been clearly associated with low SES.

Risk factors specifically associated with periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression

The pathogenesis of periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression is quite different from periodontitis with a slow/moderate rate of progression. Some risk factors like smoking, stress, and SES are the same for different forms of periodontitis but major risk factors for periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression are as follows,

Microbiological risk factors:

Bacteriology of Grade C periodontitis indicates that certain bacterial species are prevalent in these cases. Commonly isolated microorganisms from Grade C periodontitis cases include Aggeregatibactor actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens, Eikenella corrodens, Selenomonas sputigena, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Campylobacter rectus. Although the presence of these microorganisms in the periodontal pocket does not confirm periodontitis with a rapid rate of progression but their number above certain levels certainly predisposes the patient for the development of Grade C periodontitis.

Genetic and Immunological risk factors:

Many studies have demonstrated immunological abnormalities in periodontitis cases with a rapid rate of progression. Abnormalities in neutrophil functions have been proposed for rapid tissue destruction in Grade C periodontitis. It has been suggested that overly active or “primed” neutrophils may be responsible for mediating much of the tissue destruction that is observed in localized forms of Grade C periodontitis 176. Single nucleotide polymorphisms such as IL-1 gene polymorphisms have been linked to periodontal disease. Specific IL-1 genotypes have been linked to the presence of pathogenic microorganisms in rapidly progressive periodontitis cases 177. A population study demonstrated an odds ratio of 18.9 associated with a specific IL-1 genotype 178. A detailed description of cytokine polymorphism and its effect on host response has been discussed in “Role of genetics in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases”.

Diagnosis of various forms of periodontitis

The diagnosis of various forms of periodontitis is made on the basis of dental history, medical history, radiographic examination, and clinical examination. The chief complaint of the patients may not always be diagnostic of the form of periodontitis. However, relevant questions should be asked which can be useful in making a diagnosis. The past dental record of the patient is very useful in establishing a diagnosis. Any dental treatment done in the past should be recorded. Past dental treatment can be helpful in establishing the nature of dental diseases the patient is suffering from. Dental treatment in the past for chief complaints of bleeding from the gums, swollen gums, oral malodor or deep gnawing pain in the gums is indicative of past periodontal problems. The patient should be asked about any pre-existing conditions like diabetes, hypertension, smoking, use of medications and other conditions which may impact periodontal disease progression. If the patient is unable to provide adequate information, the concerned health care provider should be consulted.

After the dental and medical history is over, the routine dental and periodontal examination is done. A detailed description of history taking and clinical examination has been given in “Art of history taking in periodontics”. The patient should be thoroughly examined for all the positive dental and periodontal findings. Periodontal findings, which specifically relate to the severity of periodontal destruction and present status of disease activity include gingival examination (color, contour, consistency, surface texture, exudation or any other specific finding) and periodontal examination, which includes distribution and depth of periodontal pockets, tooth mobility, furcation involvement, recession, tooth migration or any other significant finding.

Radiographic examination is done to evaluate the amount of ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Treatment of periodontitis (general considerations)

The treatment planning of periodontitis is done on the basis of the severity and extent of periodontal involvement. The first step in the treatment of periodontitis is patient education. The patient is informed about the relationship between deposits on teeth and periodontal destruction and is educated about adequate maintenance of oral hygiene and appropriate brushing technique is instructed for oral home care. Once, the patient understands the significance of maintaining oral hygiene and is well-motivated, the treatment of periodontitis is initiated with non-surgical therapy. If required, the non-surgical therapy phase is followed by surgical therapy. Once the desired results are achieved, the patient is scheduled for supportive periodontal therapy.

Non-surgical therapy

The non-surgical therapy consists of scaling and root planing (SRP), aimed at the mechanical elimination of plaque, calculus, and other deposits. SRP is performed in multiple sittings to ensure that teeth are absolutely free from plaque and other deposits and the patient is maintaining adequate oral hygiene. A detailed description of SRP has been given in “Principles of scaling and root planing”. If the patient is not maintaining good oral hygiene, he/she should be re-informed and motivated to do so. There is evidence that in the absence of periodic professional reinforcement, self-administered plaque control programs alone are inconsistent in providing long-term inhibition of plaque-induced gingival inflammation 179-181. All the local factors which facilitate plaque accumulation (such as overhanging restorations) should be corrected so that plaque control is facilitated. It has been demonstrated that desired results are achieved when professional plaque control measures are executed along with adequate personal plaque control 182, 183. The application of self-applied or professionally applied subgingival irrigation is recommended for the reduction of bacterial load in the subgingival areas. It has been demonstrated that in patients who are not efficiently maintaining good oral hygiene, supragingival irrigation with or without anti-bacterial agent significantly reduce gingival inflammation as compared to toothbrushing alone 184.

Once, the non-surgical phase is over, there should be a marked reduction in gingival inflammation and all the signs and symptoms of inflammation should significantly reduce. The patient is re-examined for periodontal findings and further treatment is planned according to the findings. There are various therapies which can be planned if open flap debridement is not the desired treatment for the patient. These include,

Systemic antibiotic therapy

Systemic antibiotics and their combinations have been used for many years in the treatment of periodontal diseases. Systemic antibiotic treatment with a combination of metronidazole and amoxicillin has been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of periodontitis 185-187. However, it must be remembered that systemic antibiotic therapy is not indicated in all cases of periodontitis. Systemic antibiotic therapy, as an adjunct to mechanical debridement, can be utilized in specific situations such as patients with multiple sites unresponsive to mechanical debridement, acute infections, medically compromised patients, presence of tissue-invasive microorganisms and ongoing disease progression 188-191. Ideally, systemic antibiotic therapy should be instituted following bacterial culturing and sensitivity test. A detailed description of antibacterial chemotherapeutic agents has been given in “Chemotherapeutic agents used in periodontics”.

Local drug delivery (LDD)

Local delivery of therapeutic agents has been used in the treatment of periodontitis. If the patient has a few moderately deep localized pockets, LDD is the treatment of choice. This therapy includes the placement of various chemotherapeutic agents in the periodontal pocket with or without a protective dressing. The carrier/vehicle releases the agent slowly so that the effective concentration of the agent is maintained in the periodontal pocket for a desired duration of time after which it is either degraded or is removed manually. It has been demonstrated that pathogenic flora is significantly altered and periodontal pocket depth improves after the use of these agents 192-200. However, the cost-benefit ratio of LDD agents should be critically evaluated before they are applied to a particular patient. In cases where aggressive periodontal destruction is observed, LDD is not indicated and conventional therapy should be executed. A detailed description of LDD has been given in “Local drug delivery in periodontics”.

Host modulation therapy

It has been well established that during host-microbial interaction in periodontal diseases, enzymes derived from host immune cells are responsible for connective tissue destruction. Various agents have been used as host modulation agents that directly or indirectly reduce host cell-mediated connective tissue destruction 201-207. Well investigated host modulation agents include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), chemically modified tetracyclines (CMT’s) and bisphosphonates. The first United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved host modulation agent is systemically delivered collagenase inhibitor “Periostat” which contains Doxycycline Hyclate (20 mg capsule). Its application has been recommended as an adjunct to SRP in the treatment of periodontitis. Statistically, significant improvement in the periodontal status of patients has been reported with the use of Periostat 205, 207.

Overall research on host modulation agents has shown significant, but limited improvement in the periodontal status of patients. The proper protocol for the application of these agents in periodontitis cases still needs to be established. A detailed description of various host modulation agents and their clinical benefit in periodontitis patients has been given in “Host response modulation therapeutic agents in periodontics”.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

The PDT was initially introduced in the medical field for the inactivation of microorganisms on the basis of photosensitizer attachment to target cells. This therapy works on the principle of photon energy. When a photon of light is absorbed by a molecule of the photosensitizer in its ground singlet state (S), it is excited to the singlet state (S*) after it receives the energy of the photon. The lifetime of the S* state is very small (in nanosecond range) and it rapidly releases energy in the form of light (fluorescence) or by internal conversion with energy lost as heat. The photosensitizer is absorbed by microorganisms and following exposure to light of the appropriate wavelength, it becomes activated to an excited state. Then it transfers its energy from light to molecular oxygen to generate singlet oxygen and free radicals that are cytotoxic to the bacterial cells. The PDT also has stimulating effects on fibroblasts, hence helpful in wound healing. Photosensitizer molecules have been attached to antibodies directed against various periodontal pathogens.

Most of the photosensitizers used, basically have tetrapyrrole nucleus. These include porphyrins, chlorins, bacteriochlorins, and phthalocyanines. This tetrapyrrole ring structure is named porphin and derivatives of porphins are named porphyrins. Following photosensitizers are presently available for clinical use

1. Mesotetra-hydroxyphenyl-chlorine (mTHPC, temo-porfin, Foscan®; Biolitec Pharma Ltd., Dublin, Ireland).

2. Benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid A (BPD-MA, Visudyne®; QLT Inc., Vancouver, Canada and Novartis Opthalmics, Bulach, Switzerland).

3. 5- or diaminolevulinic acid (ALA, Levulan®; DUSA Phar -maceuticals Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA).

4. Methyl ester of ALA (Metvix®; Photocure ASA, Oslo, Norway).

Research on PDT has been done to evaluate its effect on the subgingival microbiota in periodontitis cases. The therapy has demonstrated bactericidal effects on subgingival periodontopathogenic bacterial species 208-213. The therapy can be used as an adjunct to non-surgical treatment modalities in the treatment of Grade A/B (chronic) periodontitis cases.

LASER application

With the introduction of LASER in dentistry, its use in different fields has been investigated. In periodontics, LASER has been used for various purposes, including debridement of root surfaces, removal of the diseased pocket epithelium, for hemostasis during surgical procedures, for its bactericidal effects and for various periodontal surgical procedures. Low-power pulsed Nd:YAG laser has been shown to be capable of removing the pocket lining epithelium in moderately deep pockets 214. LASER application has been shown to suppress and eradicate putative periodontal pathogens from periodontal pockets 215, 216. So, lasers can be effectively used in conjunction with routine SRP in the treatment of periodontitis cases with slow, moderate or rapid rate of progression.

Surgical therapy

After the execution of non-surgical therapy, if it is observed that multiple sites with moderate to deep pockets are remaining and surgical access is required to facilitate mechanical instrumentation of the root surfaces; surgical therapy is planned. The primary aims of surgical therapy are 217-219,

1. To provide better access for the removal of etiologic factors.

2. To reduce deep probing depths.

3. To regenerate or reconstruct lost periodontal tissues.

It has been well established that both non-surgical and surgical therapies are capable of halting periodontal disease progression and effectively achieve stability of clinical attachment levels 220-225. The primary advantage of surgical therapy is that it increases operators’ access to the root surfaces and furcation areas, thereby facilitating effective and efficient debridement of these surfaces 226-231. The surgical therapy provides access to bone defects, thus facilitating osseous resection and recontouring, and periodontal regenerative procedures. There are various periodontal flap surgeries described in the literature. A detailed description of these surgeries has been given in “History of surgical periodontal pocket therapy and osseous resective surgeries” and “Periodontal flap surgeries: current concepts”. Various periodontal regenerative procedures and techniques presently used in the treatment of periodontal diseases include guided tissue regeneration (GTR), bone grafting, root surface biomodification and newly introduced tissue engineering techniques.

Periodontal maintenance after active treatment of periodontitis

Once the active treatment of chronic periodontitis is over and desirable clinical results have been achieved, the patient is scheduled for the periodontal maintenance program. It involves the periodic evaluation of the patient and assessment of the results obtained from active periodontal treatment 232. The schedule for periodontal maintenance varies from patient to patient. The patients who are more prone to periodontal destruction or those who already have advanced periodontal destruction need frequent maintenance visits than patients who have minimal periodontal destruction. A detailed description of the protocol that is followed during periodontal maintenance has been given in “Periodontal maintenance”.

The above-stated treatment protocol is usually capable of controlling most of the cases of periodontitis with slight to moderate periodontal destruction and slow to moderate rate of disease progression (previously referred to as chronic periodontitis). However, in case of severe periodontal destruction and rapid rate of disease progression (previously referred to as aggressive periodontitis), more aggressive approach has to be applied to control the disease activity.

Treatment of severe periodontitis with a rapid rate of disease progression

The classical sign of Grade C periodontitis is the rapid progression of the disease which causes severe periodontal destruction in a relatively shorter duration of time. Thus, the diagnosis of the condition should be prompt and treatment planning should be done as soon as possible. Because of the difficulties in controlling the aggressive nature of the disease, the treatment of Grade C periodontitis should preferably be carried out by a periodontist. However, general practitioners play an important role in early identification of the diseases and timely referral. As discussed earlier in Grade A/B periodontitis, the treatment of Grade C periodontitis also consists of non-surgical and surgical phases.

Before any treatment is initiated, the patient is educated regarding the nature of the disease and its treatment protocol. The patient should be assured that the condition is treatable and has a good prognosis in most of the cases, provided a good patient compliance and periodontal maintenance protocol is followed. The patient should be informed about the etiological factors related to the disease, different treatment phases and probable outcome of the treatment. Most importantly, the patient should be educated regarding his/her role in the treatment of the disease. Appropriate oral hygiene instructions should be given to the patient. The patient should be educated regarding an appropriate bushing technique and other oral hygiene measures suitable for the patient. If the patient has habits such as smoking or tobacco chewing, a habit cessation protocol should be instituted.

The Stage III/IV periodontitis patients usually have some severely periodontally compromised teeth, which have a questionable prognosis. The decision should be made regarding whether to keep these teeth or to extract them. If the teeth are to be extracted, the patient should be explained about it and future restorative treatment in that area should be discussed.

Once this pre-treatment protocol is over, active periodontal treatment of the patient is started with non-surgical periodontal therapy.

Non-surgical therapy

The effectiveness of non-surgical periodontal therapy in the treatment of Grade A/B periodontitis is well established 233. However, its effectiveness in the treatment of Grade C periodontitis is not as clear as in Grade A/B periodontitis. Two aspects of non-surgical periodontal therapy that need to be assessed while determining its effectiveness in the treatment of Grade C periodontitis are changes in clinical parameters following the therapy and long-term maintenance of the results.

Slots and Rosling (1983) 234 conducted a study on six patients with localized aggressive periodontitis and treated 20 teeth associated with deep pockets with SRP. They reported a small reduction of 0.3 mm in the probing pocket depth, 16 weeks after the treatment. In another study, Kornman and Robertson (1985) 191 observed only ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Periobasics: A Textbook of Periodontics and Implantology

The book is usually delivered within one week anywhere in India and within three weeks anywhere throughout the world.

India Users:

International Users:

Systemic antibiotics

The rationale behind the systemic administration of antibiotics in Grade C periodontitis cases is to reach and destroy bacteria present in difficult to reach areas such as furcations, deeper areas of periodontal pockets and dentinal tubuli 244-246 and to reach bacteria in periodontal tissues 247, 248. Furthermore, bacteria present in areas other than periodontal tissues such as oral mucosa, tongue, and tonsils may translocate to and re-infect periodontal sites after mechanical instrumentation 249. Studies have demonstrated additional beneficial effects of adjunctive antibiotic therapy to SRP in Grade C periodontitis cases 250, 251. Whether to use antibiotics or their combinations in every case of Grade C periodontitis, choice of antibiotics and duration of therapy are still debatable questions. However, it is clear from the present data that those patients who continue to demonstrate attachment loss despite diligent mechanical therapy are prime candidates for systemic antibiotics 252-255. Although, initiation of antibiotic administration prior to or after mechanical therapy is an issue which is still being investigated 43, 250 but most of the current literature suggests that mechanical instrumentation must always precede anti-microbial therapy 256. Mombelli (2006) 257 has suggested that antibiotics should be administered only after the disruption of the bacterial biofilm. A. actinomycetemcomitans is one of the most important microorganisms involved in the etiopathogenesis of Grade C periodontitis and a combination of amoxicillin and metronidazole has been shown to be very effective in suppressing this organism to below the level of detection 186, 258-260. The recommended regimen is 250 mg of metronidazole and 375 mg of amoxicillin three times per day over a period of 7 days 189, 253, 261.

Other antibiotics investigated for the treatment of Grade C periodontitis include amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and azithromycin. Amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium has been shown to be effective in the management of localized form of Grade C periodontitis 262. Tetracyclines have been well investigated for their use in Grade C periodontitis. It has been demonstrated that systemic application of tetracycline effectively eliminates tissue bacteria and has been shown to arrest bone loss and suppress microbial levels 263. Tetracycline is used in a 250 mg 4 times daily dosage. Studies have been done to compare the effectiveness of tetracycline group of drugs with a combination of amoxicillin and metronidazole. In a study, Akincibay et al. (2008) 264 compared the clinical outcome of systemic doxycycline vs. systemic metronidazole combined with amoxicillin during scaling and root planing in localized Grade C periodontitis patients. The study included 30 patients who were randomly divided into two groups. One group received 100 mg of doxycycline once daily for 10 days and the other group received 375 mg of amoxicillin and 250 mg of metronidazole three times a day for 10 days. The results of the study demonstrated a significant clinical improvement in both the groups in terms of plaque index, gingivitis index, periodontal probing depth, and clinical attachment level values. However, the group taking metronidazole combined with amoxicillin demonstrated significantly more improvement in plaque index and gingivitis index. Although there were no significant differences between probing pocket depths and attachment levels between both groups at the end of the study, the authors observed a clear tendency for more improvement in the group taking metronidazole combined with amoxicillin.

Many randomized controlled trials have been done with a variety of antibiotics on generalized Grade C periodontitis patients, however, the combination of amoxicillin and metronidazole is becoming advocated to an increasing extent. The rationale behind the use of this combination is based on the observations 265, 266 that A. actinomycetemcomitans stains were found to be resistant to tetracycline, the antibiotic of choice for Grade C periodontitis in the 1990s. With increasing evidence regarding the inability of tetracycline to suppress A. actinomycetemcomitans, together with in-vitro data showing the synergistic effect of metronidazole and amoxicillin in inhibition of A. actinomycetemcomitans, van Winkelhoff et al. (1992) 189 designed ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Ciprofloxacin has also been used in combination with metronidazole in the treatment of Grade C periodontitis 268. This combination is very effective against mixed infections because metronidazole targets obligate anaerobes and ciprofloxacin targets facultative anaerobes. The combination reduces both obligate and facultative anaerobes and facilitates the growth of Streptococcal microflora 268. Azithromycin has been recently used for the treatment of Grade C periodontitis. The primary advantage with this drug is its long half-life which allows its once-daily dosage, thus increased patient compliance. It has been demonstrated that incomplete adherence to the antibiotic regimen adversely affects the outcome of the treatment 269. One study 241 demonstrated a significant additional 1 mm reduction in probing pocket depth and 0.7 mm gain in attachment one year after the treatment with azithromycin as an adjunct to SRP.

Local drug delivery (LDD)

There are many advantages associated with the use of LDD (read more in “Local drug delivery in periodontics”) which establish a clear rationale for their use in Grade C periodontitis. However, there is scanty literature regarding their application in Grade C periodontitis cases. One study 237 investigated the effects of SRP + 1% chlorhexidine gel (subgingivally administered) and SRP + 40% tetracycline gel (subgingivally administered) as compared to control group with only SRP. After the 12-week observation period, there was no significant improvement in clinical parameters observed in any of the test groups as compared to control group. Another study 270 was done in generalized Grade C periodontitis cases where the effect of tetracycline fibers was investigated in a split-mouth design. 10 patients were included in the study with a six-month follow-up period. The results of the study demonstrated an additional periodontal pocket depth reduction of 0.6 mm and gain of clinical attachment of 0.7 mm, up to 6 months after therapy.

Some studies have compared LDD with systemic drug delivery in Grade C periodontitis cases. In one study 271, LDD using tetracycline fibers and systemic administration of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was evaluated in Grade C periodontitis over a 52-week period in 28 patients. The therapies were started 8 weeks after completion of SRP. No significant difference was found in either treatment modality. Another study 272 compared the effect of chlorhexidine chip with systemically administered amoxicillin (1500 mg/day) plus metronidazole (750 mg/day) in generalized Grade C periodontitis cases. After six-month observation period, SRP plus adjunctive chlorhexidine chips demonstrated clinical improvement, but these were not maintained over the entire observation period. On the other hand, systemic antibiotic therapy was more effective in reducing pocket depth and gain in the clinical attachment.

Hence, it can be concluded that the use of LDD in Grade C periodontitis is not as clear as it is in the cases of Grade A/B periodontitis.

LASER application

Various studies have investigated the effectiveness of lasers as compared to other therapies in the treatment of Grade C periodontitis. One study 273 compared SRP alone, diode laser treatment (LAS) alone, and SRP combined with LAS on clinical and microbial parameters in patients with Grade C periodontitis. A 980-nm diode laser was used in continuous mode at 2 W power, in this study. The results demonstrated significant improvement in microbial and clinical parameters in patients with Grade C periodontitis over the 6-months observation period in SRP + LAS group. Another study 274 compared surgical therapy with Nd:YAG laser application in Grade C periodontitis cases. No significant difference in clinical parameters was found between the two treatment modalities. It was concluded that laser application can be used as an alternative to surgical therapy.

However, more research is required to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of lasers in Grade C periodontitis cases.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

PDT has been recently evaluated as an adjunct to SRP and an alternative to conventional surgical therapy in the treatment of Grade C periodontitis. In a study 275, the cytokine profile in GCF of Grade C (aggressive) periodontitis patients was evaluated after PDT or SRP. A split-mouth design was used in the study. The results of the study demonstrated similar effects on crevicular TNF-α and RANKL levels. Another study 276 compared the effects of PDT and systemic antibiotics in the nonsurgical treatment of Grade C periodontitis. The results of the study demonstrated significant clinical improvement with both therapies. However, systemic antibiotic therapy resulted in a significantly higher reduction of pocket depth and a lower number of deep pockets as compared to PDT.

There are only a few photodynamic studies done in Grade C periodontitis cases, most of which have shown beneficial effects of the therapy in the treatment of these cases. However, clinical data are insufficient to authenticate the exact utilization of this therapy in the treatment of Grade C (aggressive periodontitis) cases and more research is required in this direction.

Surgical therapy

As already stated, due to the aggressive nature of the disease, patients with Grade C periodontitis usually have a lot of bone loss at the time of diagnosis. Consequently, after the initial non-surgical treatment, residual pockets often remain which require surgical treatment. Furthermore, infrabony defects are usually encountered in these cases which may be suitable for regenerative therapy. Osseous corrections may also be required in certain areas. All these goals can be achieved only after surgical entry into the area.

Detailed descriptions of various flap designs used for gaining surgical access have been discussed in “History of surgical periodontal pocket therapy and osseous resective surgeries” and “Periodontal flap surgeries: current concepts”. Various studies have been done to evaluate the effectiveness of surgical therapy and its comparison with non-surgical therapy in the treatment of Grade C periodontitis. One study 277 compared SRP alone; SRP + soft tissue curettage; or, modified Widman flap surgery for treating 25 deep periodontal lesions in 7 patients. 16 weeks after the treatment, microbiological and clinical effects were ……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book……..Contents available in the book….

Mandell and Socransky (1988) 279 did a study on 8 patients with localized Grade C periodontitis. The treatment performed included modified Widman flap surgery and a doxycycline regimen. The results of the study demonstrated that the treatment done, not only effectively eliminated A. actinomycetemcomitans from periodontal pockets, but also resulted in the reduction of pocket probing depth and a mean clinical attachment gain of 1.3 mm.

These findings suggest that surgical periodontal therapy is effective in not only suppressing A. actinomycetemcomitans in periodontal pockets, but is also able to facilitate regeneration of the lost tissue. Thus, appropriate execution of surgical periodontal therapy is helpful is halting the disease progression and achieving periodontal health in Grade C (aggressive) periodontitis cases.

Regenerative therapy

As discussed earlier, various regenerative techniques such as guided tissue regeneration (GTR), bone grafting, etc. have been used to regenerate the lost periodontal structures in Grade C periodontitis. Sirirat et al. (1996) 280 in a randomized controlled trial, compared GTR and resective (osseous surgery) surgical techniques in the treatment of Grade C periodontitis. Paired defects in the same patient were included in the study, thus each patient served as their own control, thus the response to surgery and healing could be better controlled and evaluated. Twelve months after the surgical procedures it was found that the GTR group demonstrated probing depth reduction of 2.60±1.30 mm and clinical attachment gain of 2.20±1.42 mm. On the other hand, osseous surgery group showed a probing reduction of 1.73±0.96 mm and the attachment gain of 1.20±1.01 mm. Thus, GTR significantly improved the periodontal status of the patient. It must be remembered that the pattern of bone loss and type of bone defects play an important role in regenerative therapy. In general, horizontal bone loss, furcation defects, and increased tooth mobility are poor prognostic factors for regeneration 281.

The recent advancement that may be helpful in achieving regeneration in Grade C periodontitis patients is tissue-engineered biologically active molecule carrier systems. These may deliver various growth factors at the site where regeneration is desired.

Maintenance therapy

The patients with Grade C periodontitis should be motivated to provide good compliance to periodontal maintenance therapy. This is because these patients are at more risk of disease reactivation and continued periodontal destruction. A recent study has reported a mean tooth loss, of 0.13 teeth/year in patients with Grade C periodontitis 282. Furthermore, it was observed that in generalized Grade C periodontitis cases, the mean tooth loss was 0.14 teeth/ year and in localized Grade C periodontitis it was 0.02 teeth/year. The study also compared the patients who were compliant with the maintenance schedule and those who were not. It was observed that patients compliant with a maintenance schedule demonstrated loss of only 0.075 teeth/ year, whereas patients who were irregular in periodontal care had a tooth loss of 0.15 teeth/ year. Thus, periodontal maintenance is essential for the overall success of the therapy in Grade C periodontitis patients and should be planned according to the patient’s requirement. The patient should be motivated to religiously follow the maintenance schedule.

Conclusion

In the present chapter, we discussed various aspects of periodontitis including its clinical presentation and its diagnostic criteria. Along with this, we also discussed various therapeutic options that are available for the treatment of periodontitis. However, the therapeutic modality for the treatment of periodontitis in a particular patient with a particular Stage and Grade of periodontitis should be chosen carefully after considering all the risk factors associated with the patient. Disease progression is a combination of multiple factors. Most important of these factors are microbiological and immunological. Recent advances in the microbiological and immunological investigations have provided us with new methods of diagnosing and treating periodontal diseases. However, there are still many unanswered questions that need to be answered. In the future, we expect to see extensive research on periodontitis and various therapeutic modalities to treat it.

References

References available in the hard-copy of the website.